The British communications regulatory body, Ofcom, has issued its 11th annual Communications Marketing Report, and asserts that, “The millennium generation is losing its voice.” Phone calls make up only 9% of a 16-24 year old’s total communications time (compared to texting, instant messaging, email and social media, for instance). That compares to about 25% for those aged 35-64. When asked what communication and media they would miss if it was unavailable, only 3% of those aged 16-24 would miss TV, and 7% would miss phone calls, but 22% would miss text messaging.

The British communications regulatory body, Ofcom, has issued its 11th annual Communications Marketing Report, and asserts that, “The millennium generation is losing its voice.” Phone calls make up only 9% of a 16-24 year old’s total communications time (compared to texting, instant messaging, email and social media, for instance). That compares to about 25% for those aged 35-64. When asked what communication and media they would miss if it was unavailable, only 3% of those aged 16-24 would miss TV, and 7% would miss phone calls, but 22% would miss text messaging.

This is not to belittle the emerging generation, or reminisce about the good old days. When Ofcom finds that “six year olds claim to have the same understanding of communications technology as 45 year olds,” it is, however, a stark reminder that how we communicate between generations and, at a deeper level, connect as people is both amplified and attenuated by technology and other media.

Business leaders in England are complaining of the unemployability of some graduates, especially in the information technology field, that are unable to communicate with others. According to Nicola Woolcock, the education correspondent for The Times of London, “Computer science graduates have the poorest employment rates of university leavers because they struggle to communicate without using geeky language.” Simon Jenkins, noted journalist and chairman of Britain’s National Trust, wonders why we do not “Spend school time helping [students] with what appears to be holding them back in the jobs market – and in life in general? Having sat on innumerable interview panels, I groan as applicants with sound paper qualifications are painfully unable to present themselves in a group, speak well, write clearly, or show simple manners and charm.”

Business leaders in England are complaining of the unemployability of some graduates, especially in the information technology field, that are unable to communicate with others. According to Nicola Woolcock, the education correspondent for The Times of London, “Computer science graduates have the poorest employment rates of university leavers because they struggle to communicate without using geeky language.” Simon Jenkins, noted journalist and chairman of Britain’s National Trust, wonders why we do not “Spend school time helping [students] with what appears to be holding them back in the jobs market – and in life in general? Having sat on innumerable interview panels, I groan as applicants with sound paper qualifications are painfully unable to present themselves in a group, speak well, write clearly, or show simple manners and charm.”

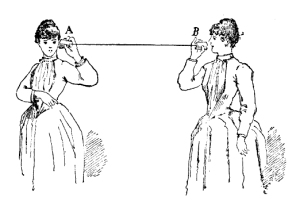

In Britain as in America there is a distracting focus on how to measure the achievement of teachers and students, rather than a loftier interpretation of education’s responsibilities, both to students and to society, to enable fully-formed individuals and citizens. Demoting the substance of educational content elides the implications of technology for inter-personal and inter-generational communication and the challenge of navigating an evolving and complicated relationship with different media. Given the importance of the capacity for communication and our ability to form genuine human connection, our practice of the art of conversation deserves more consideration in educational, social and professional contexts.